History Pages: 37 - Bridges to Somewhere: Eastside Santa Cruz in the 1870s

For a table of contents, see History pages.

Santa Cruz began as two distinct communities, separated by the San Lorenzo River. On the west side of the river was Mission Santa Cruz, with its adobe buildings arranged around the plaza on the hill, and with its farm lands on the river bottom land below.

On the east side of the river was the pueblo of Branciforte, originally planned around a never-completed plaza at today’s intersection of Branciforte Avenue and Water Street. The vee-shaped junction of Branciforte Avenue with the road to Monterey (now Soquel Avenue) became the de facto center of the eastside community. The only direct way to travel between Santa Cruz and Branciforte was to ford the river at one of several relatively wide and shallow spots. If you didn’t have a horse and/or wagon, you got your feet (at least) wet. In the winter, when it rained and the river rose, you didn’t cross at all.

All of that changed in the 1870s. The first bridge over the river was at Water Street (one of the two main fords). After a couple of short-lived attempts in the late 1860s, a more-or-less permanent bridge was completed in 1872. Next came the Soquel Avenue bridge (near the other popular ford), in 1874. Completion of the two bridges, followed by the Santa Cruz Railroad trestle in 1875, provided year-round connections between the two sides of the river. Those new connections made the east side much more desirable as a place to live and to do business.

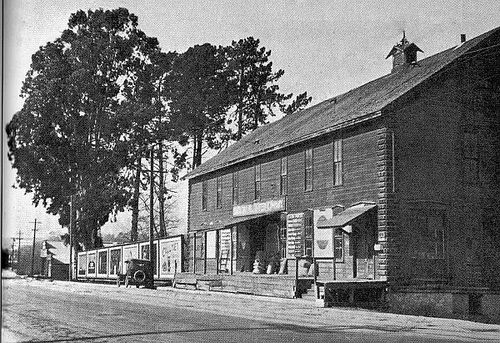

The new Soquel Bridge, in particular, opened up the area along and south of Soquel Avenue. The bridge itself had one distinctive feature – it was covered. One of only four covered bridges ever built in this county, it stood until 1921 (the earlier Powder Works and later Felton covered bridges remain). The photo here shows the west end of the bridge, sometime after a streetcar trestle was added in the early 1890s.

One theory behind covered bridges was that horses were afraid to cross high bridges (the Soquel bridge stood twenty-four feet above the river) – but, cover the bridge and the horses were OK. Another, simpler theory is that the covering protected the wood structure from the elements, increasing the life-span of the bridge.

One of the first to see new opportunities created by the bridge was the hotelier and former grocer Alfred (Fred) Barson. He bought thirty acres along the river, south of Soquel Avenue, in 1870 (today’s Barson Street was the northern boundary of the property). After the bridge opened, Barson built the Riverside Hotel in 1877 and, with his wife and children and descendents, ran it successfully until 1945. With its extensive gardens, river access and home-grown meat and produce for its restaurant, the Riverside was a unique and attractive tourist resort.

A previous post on this blog noted the hotel’s distinctive “Second Empire” architectural style, which featured the mansard roof seen in the photo at left. Access to the hotel from the bridge and Soquel Avenue was via Riverside Avenue, which soon filled up with modest but stylish new homes, many of which survive today.

A few years later, Barson made another major contribution to the city’s current configuration. He deeded to the city two rights-of-way through his land. One, running along the north boundary of his land, became Barson Street. The other (now Campbell-Riverside Street) extended from Barson Street to the riverbank. This new street became the approach to the next bridge to be built over the San Lorenzo (more on the “cut bias” bridge in future), and to today’s Riverside Avenue Bridge. The ninety-degree curved section of Riverside Avenue from Barson to Campbell and the section south of the bridge that leads to the Boardwalk came much later. If you’ve ever wondered why the bridge isn’t at the end of Ocean Street, blame Fred Barson.

Businesses also found new homes on the east side of the river, and/or increased business after the bridge was built. A large and popular one was the Henry Bausch Brewery (est.1872), located on the north side of Soquel Avenue, in the triangle formed by that street, Ocean Street and Branciforte Creek. Mr. Bausch was another of the many German immigrants who settled in Santa Cruz during this period (see History Pages #12). The Bausch Brewery was the second in town, after the Otto Diesing Brewery (1850s) on Mission Street. Unlike the Diesing Brewery, Bausch had enough land to include a German-style beer garden adjacent to the brewery, on the banks of Branciforte Creek, which became a popular social center.

A little farther from the bridge, where Soquel Avenue climbs the hill, another fashionable residential neighborhood grew up. One established Santa Cruzan who moved to this area during the 1870s was Richard Harrison Hall. Hall was a Vermonter who came to the California gold fields in 1849, but found Santa Cruz first when his ship landed here by mistake. Undeterred, Hall found his way to the gold country, but returned to Santa Cruz in 1863 and opened a butcher shop on Front Street. Prospering in that business, he bought 300 acres of land out on the Westside and established a dairy farm.

The dairy apparently also did well, and in the late 1860s or early 70s he built a new home on the Soquel Avenue grade, just below what became the corner of Ocean View Avenue, and across the street from the original Branciforte School. The house was later moved around the corner, where it remains today.

You can see the blue oval "historic" plaque in the photo.

Hall’s lot on Soquel Avenue was sold to an up-and-coming young entrepreneur named Fred Swanton, who had married Hall’s daughter. The name Swanton was destined to figure prominently in the later history of Santa Cruz, so we’ll return to him at a later date.

Just up the hill from Hall’s house, Ocean View Avenue was created in 1871 to access a hotel/boarding house called Ocean Villa, located on the bluff where Ocean View now dead-ends at the public park. Ocean Villa is prominent in an 1876 painting that can be seen at the Santa Cruz Art and History Museum. A detail from that painting can be seen at the top of this post.

Beginning shortly thereafter, and especially after construction of the Soquel Bridge, the large “ocean view” lots created along the top of the bluffs became some of the most desirable residences in town. The street still boasts probably the largest collection of large, well-preserved Victorian-era homes of any street in town.

One of the early residents and developers of Ocean View Avenue and the eastside was Martha Pilkington Wilson, a successful businesswoman and founder of what became today’s Wilson Bros. real estate company. She was instrumental in the subdivision that created Ocean View Avenue, built a home on that street in 1878, and another a few years later. The photo at right shows the first Wilson house, as it looks today after a major facelift in the 1880s.

In the following decade, the rest of the area south of Soquel Avenue, east of Ocean View as far as Seabright Avenue, was subdivided as the eastside residential neighborhood we know today. Martha Wilson and her son David were prime movers in those efforts.

Sources

- John L. Chase, The Sidewalk Companion to Santa Cruz Architecture (2005 book), Chapter 7, 3rd ed.

- History Pages: 12 - Pioneer German-Speakers of Santa Cruz County

Next: History Pages: 37 - How the Trains Came to Santa Cruz – Part 4